-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of TONY ALBERTS’s Conversations with Preston: Christmas Bells, 2020–21, acrylic and vintage appropriated fabric on canvas, 300 × 400 cm, at “Conversations with Margaret Preston,” Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney, 2021. All images courtesy the artist and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney / Singapore.

Vibrant, festive arrangements of waratahs, proteas, lilies, and desert peas belie the dark historical truths Tony Albert (Girramay/Yidinji/Kuku Yalanji) examined in his latest exhibition, “Conversations with Margaret Preston,” at Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney. Albert’s new suite of works reference painter and printmaker Margaret Preston (1875–1963) in an artistic dialogue that is both homage and critique. One of Australia’s leading modernist artists, Preston advocated for the development of a distinctly Australian culture that placed Aboriginal art at its center. Yet, however well-intentioned, her assertion that Australians “be Aboriginal” and “take” Aboriginal symbols and motifs was deeply misguided, implicitly encouraging continued acts of colonial pillaging and inspiring an array of appropriated homewares and décor. Albert is not the first artist to respond to Preston. Aboriginal artist Gordon Bennett, a significant influence for Albert, critiqued Preston’s sentiments and Aboriginal-inspired designs in his Home Décor series (1995–2013). At Sullivan+Strumpf, Albert used his personal collection of “Aboriginalia” to offer his own captivating reflection upon cultural theft and authenticity in Australia’s colonial history.

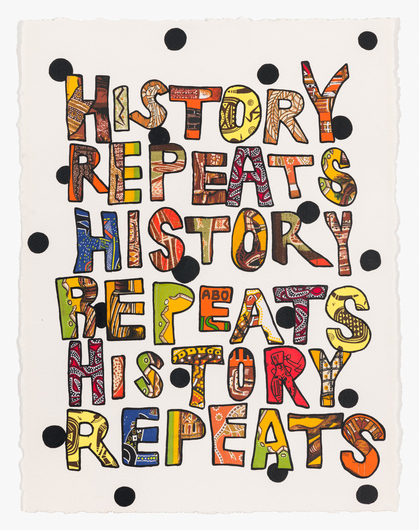

The artist has long accumulated kitsch objects bearing caricatured depictions of Aboriginal people and culture, and it is now an important element of his practice. For this exhibition the artist primarily drew upon his fabric archive. Prints bearing exaggerated Aboriginal faces along with appropriated Tiwi and Yolŋu motifs, designs from desert painting, and north Queensland shields and jawun are sliced and pasted onto canvas and paper, with black-painted borders delineating each sliver. Many replicate Preston’s print and abstract works while others, such as History Repeats and I feel the weight of the world on my shoulder (both 2020), spell out their titular phrases. A further 150 small-scale collages filled shelves upstairs. Their fabrics and fragments of Aboriginalia on red-painted backgrounds provide snapshots of concepts echoing across the exhibition. For Albert, using Aboriginalia in his works is “a kind of reconciliation with these racist objects’ very existence.” Despite being “painful reiterations of a violent and oppressive history,” he acknowledges that they are “an important societal record that should not be forgotten.” By reconstructing these problematic items into iconic, visually appealing Preston still lifes, Albert simultaneously recalls and transcends their historical trauma.

The centerpiece of the exhibition was Conversations with Preston: Christmas Bells (2020–21), which reimagines Preston’s 1925 woodblock print of the titular bell-shaped blossoms, endemic to New South Wales. At three by four meters, Albert’s collage literally and metaphorically subsumes Preston’s original. Spills of red, purple, blue, and green fabrics burst from the diptych canvases in a floral arrangement. The vase comprises a blend of tea towels depicting maps of Australia, native flora and fauna, and appropriated Aboriginal designs. Albert occasionally preserves peeks of text from the original fabrics that read “Aboriginal art.” Elsewhere the phrase is shortened to a racist slur that lurks among these seemingly innocent, decorative scenes. This gesture is again reminiscent of Bennett, who often used derogatory words or their codified markers to examine “the ethnocentric boundaries implicit in language.” By throwing these linguistic insults back at viewers, Albert commands acknowledgment of the pain imbued within these objects and the narratives they represent. Yet, their manipulation into a joyous floral composition simultaneously creates transformative potential—the possibility of a more optimistic future.

Albert’s reworkings continued in an untitled installation recreating a domestic bedroom. Neatly tucked over a cast iron bed is a quilt of t-shirts with proclamations advocating Aboriginal rights, including from artists Archie Moore (Kamilaroi) and Megan Cope (Quandamooka). Atop sits a doll made of fabrics in black, red, and yellow—colors of the Aboriginal flag—in a nod to the dolls in iconic photographs by Destiny Deacon (KuKu/Erub/Mer). Two glass lamps in the shape of male and female busts frame the bed, their titles Nguma and Yabu (both 2020) translating to “father” and “mother” in Girramay, one of Albert’s ancestral languages. The artist reclaims Preston’s reduction of Aboriginal art to décor through pieces that celebrate the collective strength of Aboriginal culture.

In Albert’s distinctly playful style, “Conversations with Margaret Preston” acknowledged the complex histories of national heroes such as Preston. By reclaiming objects haunted by trauma and shame, Albert implores viewers not to forget the histories they embody, but begin constructive conversations that can heal past wounds and offer hope. As horror swirls across Australia in response to ever-increasing Aboriginal deaths in custody and struggles to decolonize arts institutions, this dialogue is vital now more than ever.

Tony Albert’s “Conversations with Margaret Preston” is on view at Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney, until April 10, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.