-

From Issue 107

-

- Editor’s Letter Elemental Forces

- Reports Phnom Penh

- Reports Navigating Laws and Accessibility in Exhibition Practices

- Essay Man, Machine or Dragonfly?

- Profile Penelope Seidler

- Features Inas Halabi, Andrew Luk, Kim Heecheon, Karrabing Film Collective and Genevieve Chua

- Reviews Sixth Asian Art Biennial

- Reviews Ahmed Mater

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

We dream of green and blue, but live in concrete and plastic. Pixel resolutions surpass our eyes’ capacities; screens become the world. Mountains, rivers and streams appear as data points. The spirits are mostly gone, as are the fish. Can we bring these natural landscapes back? Or can we create new ones? Will we always have to irradiate ourselves to save us from the toxicity of our new environs—the ones we destroyed with such rapacious efficiency?

In imagining what the rest of the 21st century holds, we understand that detoxing, repairing and recovering from the damage we have inflicted on the world—to whatever limited extent is possible—will be the major endeavor of generations to come. Like surgeries that save the patient but also leave scars, these operations require us to forge new relationships with the earth, and with the non human creatures and the intangible presences that inhabited the planet before we asserted our ruthless dream of modernization.

As part of the magazine’s 25th-anniversary celebrations, ArtAsiaPacific introduces a new portfolio that highlights five emerging artists (defined in the broadest sense). For this inaugural feature, our editors look at four artists and an artist group whose works examine new representations of the landscape and the societal underpinnings that produce those perspectives. From Seoul, Kim Heecheon’s videos portray how deeply intertwined the virtual and actual worlds have already become through the powerful merger of technology and youth culture. The Karrabing Film Collective, based in the Northern Territory of Australia, examine the daily and historical struggles of Aboriginal communities living under the regulation and exploitation of the settler-colonialist state. The occupation of Palestine, and the environmental damage inflicted by covert Israeli operations, is examined in an ongoing project by Inas Halabi. Hong Kong’s Andrew Luk uses a homemade version of a material historically associated with destroying the landscape—napalm—along with scavenged materials to create three-dimensional abstractions commenting on modern civilization. In contrast, Genevieve Chua, from Singapore, sketches out new forms of painting through her glitched staccato notes and shaped canvases, in an evocation of the new virtual sublime. As we look ahead into what the 21st century has in store for humanity—and what we humans have in store for the planet—these five artists and groups attempt to reframe our many relationships to the landscape, in processes of physical and psychic therapy. HGM

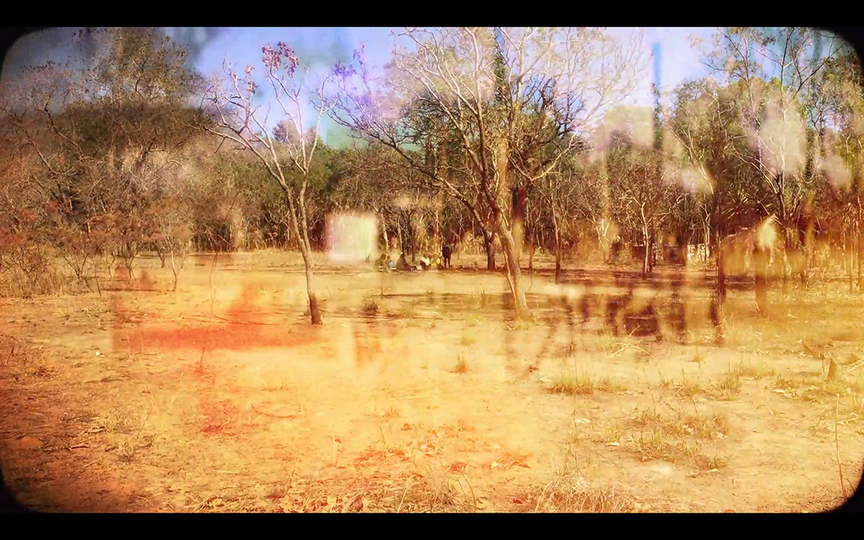

INAS HALABI, Lions Warn of Futures Present, 2017, digital image captured behind three red plastic sheets in Tarqoumia, south of the West Bank, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Inas Halabi

When Palestinian artist Inas Halabi asked family members to tell the story of how her grandfather received a scar on his forehead, they provided differing narratives. She recorded the various accounts for Mnemosyne (2016), a video installation commissioned for the London- and Ramallah-based AM Qattan Foundation’s Young Artist of the Year Award in 2016. Melding her family chronicles with those of her homeland, Halabi undermines the idea that defining moments carry a fixed history.

Moving into more ambitious territory to probe humanity’s effect on the natural landscape and collective trauma, the artist has been working on the ongoing photo-video project Lions Warn of Futures Present (2017– ), which was commissioned for Sharjah Biennial 13’s offsite project in Ramallah.

Expanding on research by nuclear-physics specialist Khalil Thabayneh, who visited Palestinian and Bedouin lands to look into the extraordinarily high levels of cesium-137—an element that can only be created during nuclear fission—Halabi shows us secret chemical-waste burial sites outside of Hebron, located north of Israel’s Negev Nuclear Research Center. Those born in these areas experience high rates of cancers, tumors and birth defects. To visualize the damaging radiation, Halabi recorded images of these lands with red plastic wrapped over her camera’s lens, the layers’ thicknesses corresponding to cesium levels where she stood. Lions is now being developed into a film, which will be shown this spring by the Greek arts organization Locus Athens. BN

ANDREW LUK, Horizon Scan No. 5, 2017, epoxy resin, polystyrene plastic and canvas on board with edge-lit LED lights, 60 × 200 cm. Courtesy the artist and de Sarthe Gallery, Hong Kong/Beijing.

Andrew Luk

From afar, one sees a lunar surface: craggy, alluvial and glimmering with extraterrestrial detritus. Up close, the layers begin to shift: we spot the flat, hard plane of metal against an orange, fibrous material, and a glossy smattering of micro-bubbles floating in resin. A light from behind casts gradual tonal variations on the landscape. Yet it’s not a slice of the moon after all, but a self-enclosed scenery created by Hong Kong-based Andrew Luk. Exposing found material to homemade napalm—a violently flammable chemical that recalls conflicts and trauma of the past century—the artist lets the resulting layers settle and melt onto each other, pushing an awareness of the self-inflicted, warped scars that exist in our social and physical terrains. The topographical, historical studies latent in Luk’s ongoing “Horizon Scan” series (2017– ) reveal an eight-year practice that merges classical sculpture and research into accumulated narratives, whether exploring urban palimpsests, or so-called natural phenomena that are, in fact, byproducts of modern development. In 2017, for a duo show at Neptune, a shop stall in a tiny 1970s-era social housing block in Hong Kong, Luk extended the space with a rock of engorged, day-glo-blue-painted spray foam. The work was titled after and inspired by the phenomenon of “blue ice,” in which chunks of frozen sewage leaks and falls from the lavatories of aircrafts, creating an otherworldly looking “asteroid” pattern that is, in actuality, human-produced waste. YC

KIM HEECHEON, Sleigh Ride Chill, 2016, still from single-channel video with color and sound: 4 min 57 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Kim Heecheon

“Why are they so obsessed with using each other as memes? Bending the connecting band between each other into a globe,” asks a digitally manipulated voice in the fragmented language that runs throughout architect, artist and filmmaker Kim Heecheon’s video Sleigh Ride Chill (2016). The anonymous narrator is referring to what happened to a girl he supposedly knew when her sex tape was leaked online—one of the three storylines in the work that probe the ways in which the internet, video games and virtual reality reflect and affect contemporary Korean society. Dizzying footage of Seoul’s bustling nightscape is intercut with face-swapped videos and rollercoaster rides as the other threads, centered around a suicide club and a soliloquy about the future, delivered via a livestream of an online game by one of the players, are revealed. The interwoven elements make apparent that the narrator’s statement applies broadly to global perceptions of distance, suggesting that how we see and relate to each other parallels morphing technologies.

Such concerns are also reflected in Kim’s more recent videos, such as Home (2017), the centerpiece to the artist’s solo exhibition at Doosan Gallery, Seoul, in 2017, which portrays Seoul through the lens of seichi junrei—a type of tourism that takes anime fans to the real-life locations that the shows are based on. Kim’s works are critical of how digital landscapes overlap with our sense of reality. Far from being superficially celebratory of emerging technologies, he captures a sense of anxiety that comes with the invention of the new. CC

Karrabing Film Collective

The videos of the Karrabing Film Collective portray the multiple realities of life for Indigenous communities in Australia’s Northern Territory, from their confrontations with agents of the settler-colonialist Australian state, to disagreements between families, and the specific places and the figures of the Dreaming, a worldview held by Aboriginal communities that connects the spiritual and natural world. The collective dates back to 2007, when police and the military intervened into Aboriginal communities, tightening state control over daily life. Karrabing, a self-described “form of survivance,” was initiated to bring in revenue for the community and as an experiment in self-organized cultural production.

Reframing the world through an Indigenous perspective that articulates a relationship to the natural environment developed across millennia, the collective creates their films through an improvisational method that allows them to reflect upon and describe their communities’ fractured existence. Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams (2016), for instance, centers around the story of a boat that breaks down, leaving members of an extended family stranded. The events are retold through flashbacks as family members debate what caused it—whether it was a mechanical fault or if their ancestors were punishing them—and if it could have been fixed by faith in Jesus. The film portrays each perspective, collaged together with filmic visualizations of the Dreaming. Eschewing the isolation of traditionalism, Karrabing explains: “Instead of going backward, we’re going on and teaching our kids to continue the stories for the next generation to the next.” HGM

GENEVIEVE CHUA, Mnemonic, Staccato 5, 2016, from the series “Mnemonic, Staccato,” 2015–16, acrylic and screen print with enamel on shaped canvases, 36 × 34.5 × 4.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Genevieve Chua

As a painter, Genevieve Chua is beholden to reinventing the forms of surfaces she uses and the strokes she imparts on them. The Singaporean artist torques and shapes her canvases to break down the formalities of traditional painting and create a new kind of carte blanche space in which to discuss evolutionary progressions, or changes in landscapes initiated by natural incidents such as flooding.

For example, in her “Swivel” series (2014–17), she reinforces her delicate pieces with a skeletal steel frame, creating kinetic mobiles that simultaneously confront and turn away from a visitor’s gaze. On their surfaces, she has painted and printed glitch-like marks that represent the often invisible under-painting processes of artists as well as futuristic geographies. In another painting series, the monochrome “Mnemonic, Staccato” (2015–16), the clustered dot marks become scores through which one might read rhythmic tappings before a lull of silence, resembling harmonious Morse code or abstract communications that make up a futuristic mountain, valley or field of sound, as the world is transformed into more versions of data to process. YC

SUBSCRIBE NOW to receive ArtAsiaPacific’s print editions, including the current issue with this article, for only USD 85 a year or USD 160 for two years.

ORDER the print edition of the March/April 2018 issue, in which this article is printed, for USD 15.