R

E

V N

E

X

T

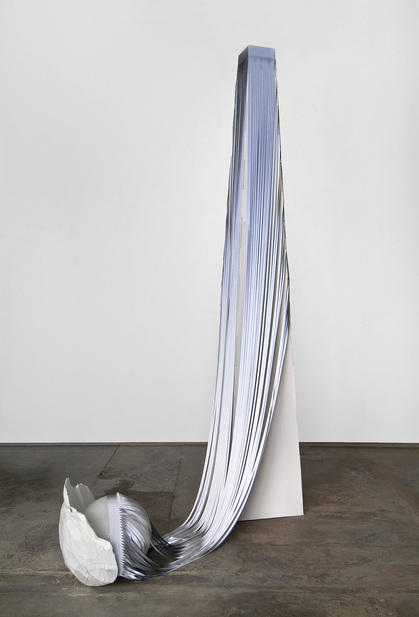

SHIRLEY TSE, Negotiated Differences (detail), 2019, 3D-printed forms in wood, carved wood, metal, and plastic. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy the artist and M+, Hong Kong.

Styrofoam boxes, nylon bags and recycled rubber are not just the materials of Shirley Tse’s sculptures; they are the subjects too. Born in Hong Kong and residing in the United States since 1992, Tse has been fascinated by the material histories of plastics and polymers for three decades. For the artist, mass-produced materials reflect our cultural desires as well as the economic and political realities of modern society. Her sculptural and installation works bring to the fore the significance of these materials in our contemporary world—how we depend on them, and how the movements of people and patterns of trade are affected and reflected by their proliferation—while also demonstrating the materials’ metaphoric potential.

Beginning in the late 1990s, her installations of oddly shaped packaging molds such as Polymathicstyrene and her photographic series “Diaspora? Touristy?” of bubble wrap shaped like minimalist sculptures and deployed in natural settings, use what the artist calls the “residue” of movement and migration to give form to the phenomenon of globalization. Continuing her investigation of plastic’s unavoidable sociopolitical ties, Tse turned to the complex and often contradictory ideas inherent in the material to explore the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics in her series “Quantum Shirley” (2007– ).

In March, ArtAsiaPacific spoke with the artist about her decades-long practice and her new series of objects fashioned from wood, “Stakeholders,” which will debut at the 58th Venice Biennale in May at the Hong Kong Pavilion, co-presented by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council and M+, and guest curated by Christina Li.

In your early works, you used readymade objects such as polystyrene foam insulation, vinyl sheets and bubble wrap—some of which were by-products of manufactured objects. What led you to explore plastic as a sculptural material?

Throughout the 1990s, I had questions about the machine-made aesthetic. I wanted to understand what determined the forms of mass-produced objects, because, to me, they look quite mysterious. Sometimes, when looking at the shape of a standardized plastic object, it’s clear that the shape is not determined by human decision alone. Take the Tetris-like foam packaging of computers and televisions, for example. While studying at Berkeley in the early 1990s, I began working with Styrofoam, and later I extended my research on the various types of synthetic polymers, more commonly known as plastic.

Through the ages, plastic has shifted through different ideologies; it’s a prime signifier of globalization and movement. In the beginning, it was created as a simulacrum of natural materials, specifically ivory and tortoise-shell, offering some sort of democratic ideal. Since it’s much cheaper, more people could afford the alternative to these otherwise luxurious, scarce natural materials. Later it became a thing in itself without a counterpart in nature. Researching the history of plastics led me to move away from focusing on plastic as a noun, to looking at plastic as an adjective.

Since my exhibition “Sink Like a Submarine” in 2007, which examined plastic’s role in the military and oil industries, I’ve expanded my practice to working with other materials such as metals, glass and paper, exploring the ideas of plasticity and multiplicity. I also studied the chemistry of plastics and found that they are petroleum-derived products made of carbon. So in fact, they’re organic! What makes it plastic is the organization of the molecule—the syntax, the structure. The synthetic action of putting the molecule together is plastic, meaning plastic is a code. That blew my mind.

Because they are so fundamental to our lives, plastics intersect with all kinds of industries and histories, many of them quite exploitative, in terms of labor, consumerism, warfare and colonialism—not to mention the environmental toll of plastic. Was there always a political urgency behind your interest in plastic?

There came a time when politics just couldn’t be ignored. Early in my career, I was so naive—I thought that art was an innocent creative pursuit. I had no idea that it was so intricately linked to commerce, economics and politics. I was young and living in New York, and was working for the shoe company British Knights as a junior designer. This was around 1991, when all the shoe factories moved away from South Korea into China to cut labor costs, and I was promoted quickly because I was bilingual. My boss invited me to an executive meeting, and they were discussing how the sales were great in the Bronx because the company’s acronym BK was co-opted by the Los Angeles Crips gang to stand for “Blood Killer.” It took me a while to understand this and it hit me hard because I realized that I still had much to learn about how things were so interconnected. That’s when I decided to pursue an MFA at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California.

You had a peripatetic period in your life, in which you moved between Hong Kong and New York, California and Chicago. How did your itinerancy and the different environments impact your artistic practice?

I needed to move to further myself. When you look at my practice, the work really does change over the years and reflects my personal moves geographically. Through my experience of living in different places and cultures, I realized that a lot of what we take for granted is totally artificial. There’s no standard because people live across various locations, cultures, ideologies and beliefs. The social contract for how you should behave is completely dependent on where you are. You can shift your own beliefs and ideologies to fit into the place you are moving to, or you can bring your beliefs and ideologies with you and be different. So, you see, there’s a negotiation happening within your own value system.

That brings to mind a quote by Ralph Rugoff, the 58th Venice Biennale’s curator—that we are in a moment where reality is being treated as a “malleable” idea. Are there any works in the forthcoming Hong Kong Pavilion that play with this idea

of reality?

There’s one smaller work in the Biennale project that is part of my ongoing “Quantum Shirley” project (2007– ), which I began as a process to understand my personal story and Chinese diasporic journey. It’s a shuttlecock made with rubber and vanilla bean pods, shown as part of the outdoor installation Playcourt (2019). I envisioned it installed in the courtyard in Venice, because that’s where the idea came to me—I was reminded of the architectural spaces in Hong Kong where I grew up playing badminton.

To give some background, I’m the fourth kid in my family. My mother, who is Chinese, was born in Malaysia because her family moved there from China many generations ago to work in a rubber plantation managed by the British colonial settlements. When the job market became saturated, a part of her family moved to Tahiti to work in the vanilla plantation farms owned by the French. In the year I was born, my second cousin, who lives in Tahiti and is a toy merchant, visited Hong Kong, and knowing my family’s financial hardships, offered to adopt me as a baby—it’s quite common for Chinese families to help each other this way. Needless to say, it didn’t happen!

When I found out that shuttlecocks are made of rubber, and that the current variation of badminton had developed over centuries with links to the ancient Chinese game jianzi, and more recently during the British Colonial period in the 1860s in India, it made a lot of sense to make this sculpture. I made my own rubber base and used vanilla bean pods instead of feathers. The work is simultaneously personal, about my childhood in Hong Kong, but also about the colonial trade routes that affect the lives of countless families. I also liked the sculptural image of the shuttlecock shuttling between two places, referencing diaspora, trading and movement.

What were the origins of the “Quantum Shirley” series? And what links are there between quantum physics and the other topics you were interested in?

The “Quantum Shirley” series began when I was studying molecules of plastic, which then led me to look at quantum physics and the theory of parallel universes. Physicists use the example of a playing card—if it falls, it actually lands on both sides, but we only have access to one of them because of our own point of observation. Since then, this image of multiple worlds coexisting simultaneously has been in the back of my mind, and it made me question my own reality. The series began with a sculpture, Superposition (2009), which comprises an eight-of-diamonds playing card held up by a wave and a cloud. It takes the idea quite literally: the cloud represents Hong Kong, and the block of ocean stands for Tahiti.

It might sound silly but I couldn’t shake this idea. What are the chances that I am fascinated with plastic, and my mother had harvested rubber trees before I was born? And what are the chances that my mother, who’s Chinese but Malaysian-born, ended up in Hong Kong, later meeting a cousin from Tahiti and talking about the toy industry? My mother had left mainland China as a student during the Cultural Revolution and became a refugee in Hong Kong—but remember, she’s not really from China, she’s from Malaysia. Had the timeline shifted and my second cousin visited ten years later, the toy factories would have already moved from Hong Kong to China. In 2002, when I visited my second cousin in Tahiti, she gave me a calendar as a souvenir—flipping it over, I saw a sticker that said “Printed in Hong Kong.” Do you see the convergence of all these events? It’s at the intersection of the personal, historical, political and socio-economical. There’s a plasticity involved in this narrative, and I couldn’t ignore it.

Foreground: SUPERPOSITION, 2009, from the “Quantum Shirley” series (2007– ), foam core, polystyrene, digital print, paint, metal, 106 × 259 × 152 cm. Photo by Gene Ogami. Courtesy the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica.

Background: DOUBLE COMFORT OF SOFT FILLED SPACE, 2009, from the “Quantum Shirley” series (2007– ), polystyrene, fiberboard, dimensions variable. Photo by Gene Ogami. Courtesy the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica.

How are these ideas of plasticity and convergence reflected in the works you are exhibiting in the Hong Kong Pavilion at Venice?

“Stakeholders” is a continuation of my ideas about differences and multiplicity from my early days of working with plastic, though they are rendered in a host of materials. An indoor installation titled Negotiated Differences (2019) will include an installation of various representational and abstract shapes, which I carved from either natural or composite wood on a motorized lathe or by hand. These shapes are all connected by 3D-printed metal or plastic joints. I see the whole form as a kind of organic creature, like a rhizome, spreading through the pavilion space. There is also an auditory component in the outdoor courtyard, where there will be several antennas picking up the region’s amateur radio broadcasting signals.

This idea of the rhizome, with its roots and nodes, also relates to your practice of examining sculptural processes as models of multidimensional thinking. Could you elaborate on how this might be reflected in the exhibition’s layout?

The installation is going to spread out and obstruct one of the archways in the pavilion so you cannot simply walk through the structure, but you will be forced to go around and look at the work from different angles. The key idea here is that although there is a forced perspective, there is no privileged viewpoint. Another concept of the installation is to not privilege the sophistication of craft, but to also display amateur skills. I purposefully included some of the really rough marks left by my hand holding a chisel in an unsure way. At the same time, there are shapes that look completely seamless to the point where you cannot see any traces of the craft.

This nonhierarchical strategy recognizes multiple perspectives and interpretations, but could also allow viewers to see the various shapes as stand-alone objects. What was your process for selecting the different shapes and motifs?

My works are never inspired by one single thing—they’re the products of multiple ideas and influences coming together. In the beginning, I didn’t plan for exactly what I was going to include, but I had a mental checklist to show a multiplicity of abstract and representational objects. Among the abstract elements, the object might refer to the process itself or other art historical examples, like Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column. Within the representational category, I wanted to include indoor and outdoor objects, musical instruments, sporting goods, architectural details, and Western, Chinese and Moroccan furniture. I then improvised the different shapes, as well as including specific objects that were significant in my life, or things that I chanced upon during my period of creating the installation.

When you look at the work, you might see a block of wood, a prosthetic leg or even bowling pins. When I was growing up in Hong Kong, bowling and badminton were favorite pastimes. The significance of a bowling pin is twofold. Firstly, I wanted to play with spatial illusion. The bowling pins are carved in different sizes—the pins closer to you are larger and the ones further away are smaller—so it’s as if the pins are tumbling up in the air, frozen upon impact, like you are looking at them from the “wrong” perspective. Secondly, because the concept of the piece is about multiplicity and how differences negotiate and coexist with one another, I wanted to have the contrast between objects that indicate motion and objects that suggest stability. For example, sport versus something that is more static, like a table leg.

Some of the furniture elements come from my research into the lathe, and its wide use in Africa and the Middle East. I recently visited Morocco with my sister, and in one of the souks I witnessed a craftsman carving an incredible decorative honey-dipper. With one hand he was using a bow to turn the block of wood back and forth, and with his bare feet he was operating the chisel. I was stunned. I knew I had to re-create the object and include it here. In wood-turning class, I learned spindle turning, and so that’s how many of the pieces were made. I also wanted to show the multiplicity of wood types and colors, so the objects are presented in their natural color and not stained. Other wood pieces were not turned on a lathe but carved by hand. I learned that Chinese table legs were mostly hand-carved and square in form, so the installation references Ming Dynasty furniture.

There’s also a gavel, because while I was creating this installation, in November 2018, there was an election in the US where the Democrats won back the House of Representatives. When I saw that Nancy Pelosi reclaimed the House Speaker’s gavel, I had to create a gavel the next day—how could I not? Some other objects that are included are a shoe last and a badminton racket—both of which are self-referential. Other objects are not one-to-one scale, like the oversized tampon dispenser. There’s also a gondola oar, because the installation will be shown in Venice. So, there was really a lot of process and movement involved in the decision of what I was going to carve, and the installation was not predetermined. In a way, the work is a visual diary. That’s really important to me.

Earlier, you mentioned that there will also be antennas in the pavilion’s courtyard. What will these antennas do, and what was your reason for positioning them there?

In Playcourt, several vertical antennas are installed outdoors and they’ll pick up amateur (ham) radio frequencies from around the region. Ham radio allows people to talk to each other across cities, countries and even into space, without the use of the internet or mobile devices. I wanted to use the verticality of the antennas to draw the viewer’s eye to the clothing line that is currently there, to emphasize the venue’s domestic quality.

When I visited the pavilion’s location, it was interesting to stand in the outdoor courtyard and listen to the sounds of Venice: washing machines, people’s echoing footsteps, voices. The enclosed structure brought back a lot of memories of residential areas in Hong Kong where I grew up. I wanted to include something unrehearsed, and one of the important concepts in the work I want to highlight is non-predetermined action. Something that you cannot predict.

I don’t necessarily use my art to express myself anymore. At a certain point, I moved beyond that approach. My work no longer became about me, but of course, that’s also not easy to say, because in the end the work is always going to reflect you—the way you think, your point of view, and perhaps unknowingly, your history too.

SUBSCRIBE NOW to receive ArtAsiaPacific’s print editions, including the current issue with this article, for only USD 85 a year or USD 160 for two years.

ORDER the print edition of the May/June 2019 issue, in which this article is printed, for USD 15.