-

From Issue 117

-

- Editor’s Letter On the Other Side of Fear

- One On One Tuan Andrew Nguyen on Daniel Joseph Martinez

- The Point Remember when contemporary art solved the climate crisis?

- Profiles Chloe Suen

- Features Will It Return?

- Reviews Martha Atienza

- Reviews Phantom Plane: Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of HUANG YONG PING’s Serpent d’Océan, 2012, permanent in-situ installation of aluminum and iron, 125 × 4 × 4 m, at “Estuaire Nantes<>Saint-Nazaire,” Saint-Brévin-les-Pins, France, 2012. Copyright ADAGP Huang Yong Ping. Photo by Gino Maccarinelli / LVAN. Courtesy the artist; Le Voyage à Nantes; and kamel mennour, Paris / London.

On Serpent d’Océan by Huang Yong Ping, or, a way to remember a master of our time.

There are very few contemporary artworks that have returned after their physical disappearance. Among these legendary works, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), in the Great Salt Lake of Utah, is certainly the most famous, and remains shrouded in mystery. A spiral of stones and mud that was covered by water for decades, it is a monument of both utopia and dystopia, a testimony to the triumph of humans over nature and our capitulation to entropy. Half a century later, and across the Atlantic, Huang Yong Ping’s Serpent d’Océan (2012) resurrects the mystery of the return, while at the same time launching a new legend about the unstoppable power of entropy. In this case, the legend refers to both the natural world and human society. More precisely, this incarnation represents how entropic metamorphosis mingles with and transforms nature—including animals and humans—as civilization carries the planet into the Anthropocene era, leaving us speculating on what “post-human” means and what our future will bring.

Serpent d’Océan is an immense skeleton of a serpent, cast in aluminum and 130 meters long, its spindly ribs planted in the water near the beachhead of Saint-Brevin-les-Pins on the French coast. Obeying the rhythm of the tides, the gigantic snake is alternatively immersed in the Atlantic and reappears every few hours. As with the tide, it recedes and returns infinitely. When looking at the work, one can’t help but ask: Where does this serpent come from? Why is it here, at the estuary where the ocean merges with the Loire? Where will it go afterward? One obvious resemblance is to the figure of the migrant, whether human or animal, or a material thing. Over time, the snake’s “body,” or skeleton, is eroded while also growing a new skin of maritime species. Like a living fossil, it testifies to the formation of a new geological layer, albeit one applied to a human-made “animal.” And although it never existed as a real serpent with skin and flesh, with these processes of accumulation and abrasion, the skeleton now has its own life cycle.

Installation view of Theatre du Monde – Le Pont, 1993–95, cages (metal, wood), bronzes from the collections of Cernuschi Museum in Paris, tortoises, snakes, insects, 10.4 × 3.2 × 1.8 m at “Galerie des Cinq Continents,” Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie, Paris, 1995–96. Copyright ADAGP Huang Yong Ping. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Central to the project, as well as to Huang’s work at large, is the belief that “changing is the rule,” emphasizing that movement, migration, transformation, and metamorphosis are the essence of existence. The serpent, constantly moving, traveling energetically but quasi-invisibly, and periodically transforming itself through molting, represents perfectly this “truth of existence.” A believer in paradox and uncertainty as the ultimate modes of understanding the world, Huang sees the boundaries separating humans and other “creatures”—animals, plants, and all natural elements—as meaningless, while the fate of existence is simply beyond our grasp. He was always deeply fascinated by the serpent’s “way of living,” or life cycle, and explored the complex implications and impacts of its symbolism—often representing supernatural and magical powers, haunted by a certain quality of evil. As a motif and symbol, the snake, or serpent, has traveled through myriad cultures, times, and systems of belief, from ancient China, ancient Egypt, and Judeo-Christian religions to Indian cults, and today can be used to evoke situations ranging from particular geopolitical realities to global capitalism.

Huang’s obsession with the serpent was initiated in a specific project inspired by social and geopolitical events. In 1993, for his first project realized in the United States, at the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University, he revealed the fate of “illegal” Chinese immigrants trafficked by human smugglers to the US with an installation featuring a giant rope-net trap. In the Fujian dialect, the artist’s mother tongue, the immigrants were referred to as “human snakes” and the traffickers “snake heads.” Since then, Huang has incorporated the image of the serpent as a central figure in his work, mostly in the form of skeletons.

At least 23 works in Huang’s oeuvre utilize the image of the serpent. A selected list reveals the associations he drew from the figure, beginning with the Human Snake (1993), which denounced the contradictory attitude of the US toward Chinese immigrants. In 1995, at the Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie in Paris, he introduced live snakes and other reptiles in his installation Théâtre du Monde – Le Pont (Theater of the World – The Bridge), in order to demonstrate the inevitable, mutual consumption of all creatures, leading to extinction, as the truth of coexistence in the world. Palanquin, his 1997 sculpture of a sedan chair adorned with molted snakeskin and a pith helmet but absent of any figures, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, pointed to the ultimate demise of colonialism. For the France Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1999, “Un Homme, Neuf Animaux” (“One Man, Nine Animals”), the serpent and other mythical animals represented in Huang’s installation were derived from the classic Chinese text Shan Hai Jing (The Book of Mountains and Oceans), and predicted unending conflict as the future of the world. In 2000, Python introduced the Chinese idea of feng shui to “reconfigure” the natural environment of a small German town, with a wooden snake skeleton installed alongside the river. The creature’s spine was reintroduced at the Walker Art Center, cutting through the spaces of Huang’s midcareer retrospective, “House of Oracles,” in 2005. At Gladstone Gallery in New York, in 2009, Huang created a dystopian version of a Tower of Babel, with bamboo columns supporting a metal structure in the form of a snake skeleton on which the audience was invited to climb, for the installation Tower Snake. In the same year, his Arche at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, recreated Noah’s Ark, using the remains of naturalized animals collected from a taxidermy workshop destroyed by fire, with serpents and other animals forming a contemporary apocalyptic scene.

The giant serpent skeleton reappeared in Ressort (2012), at the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, for the 7th Asia Pacific Triennial, having navigated the oceans only to emerge in the southern hemisphere and soar over the main hall of the museum. In the meantime, Serpent d’Océan, resonating with the fate of migrants, landed at Saint-Brevin-les-Pins for the Estuaire festival of public artworks. A couple of years later, Mue de Serpent (2014), shown at Galerie HAB in nearby Nantes, was the molt of the snake, recalling the continuing transformation of Serpent d’Océan.

Installation view of Bâton Serpent, 2014, aluminum, inox, 53 m, at “Bâton Serpent,” MAXXI, Rome, 2014–15. Copyright ADAGP Huang Yong Ping. Photo by M3 Studio. Courtesy the artist; MAXXI, Rome; Red Brick Art Museum, Beijing; and kamel mennour, Paris / London.

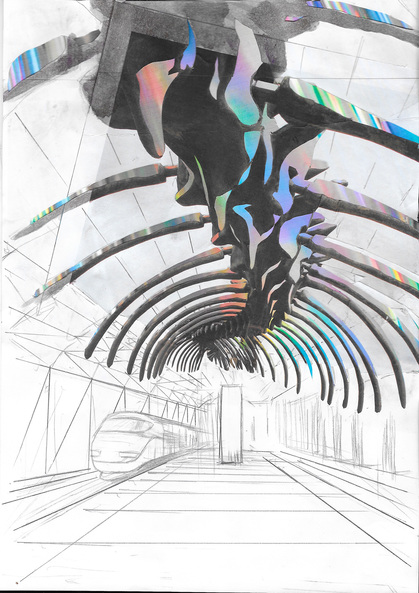

Beginning in 2015, Huang’s Bâton Serpent series became symbols for grand ideologies. Bâton Serpent, at MAXXI in Rome, turned Moses’s miraculous staff into a huge serpent, provoking subversive readings of religious dogmas in the context of Rome as the capital of the Catholic Church. In 2016, in Bâton Serpent II, at the Red Brick Art Museum in Beijing, Huang made the serpent a marker of the controversial “Air Defense Identification Zone,” which China imposed over its neighbors and the region’s disputed territories. In Bâton Serpent III: Spur Track to the Left (2016), the serpent became a symbol of the political changes in China and the world. Finally, in Empires (2016), part of the Monumenta installation series at the Grand Palais in Paris, the serpent served as an omnipresent image of the fate of globalization and its impact. When Huang died unexpectedly in October 2019, he left behind another massive project, Rainbow Snake, for the new Haga Station in Gothenburg, Sweden. Planned for completion in a couple of years, its final realization is now uncertain. But it too will certainly retain its mythical nature.

The real meaning of the serpent can never be thoroughly comprehended, since it is always moving and changing. Nevertheless, it always leads to the revelation of miracles. Commenting on his utilization of the form for his 2014–15 exhibition “Bâton Serpent” at the MAXXI, Huang evoked the Biblical legend of Exodus, in which Moses transformed his staff into a serpent to manifest the power of God:

Of course, the title of my work, just like the legend I quoted, can be seen as a trap, set intentionally, or perhaps unintentionally. This trap is for people who desire to know more. It’s like asking a question; especially when the work itself looks ambiguous, they mistake the title for a road sign. In art, the road sign often appears before the road is built; in other words, it’s like erecting a road sign in a place without a road. Legends are the same. In Genesis, the first book of the Bible, and in Revelations, the final book, the image of the serpent represents “evil.” Since “evil” is indispensable in both the creation of religion and the creation of the world, we should have a new understanding of “evilness.” However, this is neither the first nor the last appearance of the “Serpent” in my work. Like time itself, it’s both eternal and endless.

The gigantic serpent of Empires, nearly 300 meters in length, crawled over 300 shipping containers, under a giant Napoleonic bicorne hat and cut through the very axis of Paris, midway between the Champs-Elysées and Les Invalides. The serpent’s continuous travel and transformation led to an ultimately spectacular representation of the contradictory forces of globalization by exploring and uncovering its historical roots and routes—revealing how revolution, colonialism, transnational capitalism, and contemporary forms of totalitarianism have come together to form a monster called the “global empire.” Echoing philosophers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s treatise on the contemporary political order, Empire (2000), Huang’s serpent becomes a wake-up call for us to trace the very destiny of the world that we have created. Once the Monumenta show ended, did the serpent disappear back into the ocean? When and where will it emerge again?

Huang Yong Ping departed this world a few months ago, leaving this question unanswered. But probably the best thing we can do is to not try to answer it. Instead, let’s sit next to his Serpent d’Océan, whenever we want, and wait for the tide to retreat and then return.

SUBSCRIBE NOW to receive ArtAsiaPacific’s print editions, including the current issue with this article, for only USD 95 a year or USD 180 for two years.

ORDER the print edition of the March/April 2020 issue, in which this article is printed, for USD 20.