R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of The Spiral, 2019, single-channel video installation with sound: 7 min 10 sec, at “Hold Everything Dear,” The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, 2019–20. All images courtesy the artist.

You step into the darkness. You look up, and through the layers of leaves, in the night sky, there is light. As you begin to move, a voice speaks. “The spiral is much more than just a form . . . It expands and contracts, increases and decreases . . . it is the form of smoke entering the air . . .” She finds the form in nature, and in ourselves. “The form of embryos and the cylindrical helices of our umbilical cords that tether mother to child.” The outlines of silhouetted leaves change above you. “It reminds us that just as everything comes together, everything falls apart again . . .” She evokes its deeper significations. “It is a way of seeing . . . It is about community / collaboration / attaching and being attached . . . Change, is rarely a straightforward line.” Is she talking to you, or are these your own thoughts?

The motion of this seven-minute filmic journey through the dark is a mysterious one. Initially the words might seem to echo Rebecca Solnit’s reflection on walking as the “state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned” but the visual motion is a smooth one, without acceleration or resistance, a voyage more of mind or metaphor rather than body and earth. Hajra Waheed debuted this poem-video The Spiral (2019) in September 2019 at her solo exhibition “Hold Everything Dear” at the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, where more than 100 works—spanning collages to ceramics, etchings to cyanotypes on fabric—suggested that she was tracing new lines of flight within her practice, connecting people and places across time in a process that she describes in The Spiral as one originating in “the awareness of the self and the expansion of this awareness outwards.”

For more than a decade leading up to “Hold Everything Dear,” Waheed’s practice has pivoted around an allusive yet calculated manipulation of found materials, re-presenting them as categorical-seeming records that at times confound and at other times reveal. For her, the materials she employs—old paper stock, typewritten documents, vintage photographs, archival moving images—possess a “pre-supposed and embedded history.” Her work “always starts from the same place, with a process of excavation, of unearthing forgotten stories,” she explained in a video for the 2016 edition of Canada’s national Sobey Art Award, “Then cutting, splicing, and reconstructing them to destabilize official narratives in the hopes of reclaiming what is lost, in order to reimagine what is to come.” Squinting at the series of 28 diptych collages The ARD: Study for a Portrait 1–28 (2018), for instance, we register distantly captured figures that a terse description printed below indicates are Saudi oil workers organizing a bus boycott in 1955; and a curl of smoke, marked with a hand-drawn X, rising behind newly built tract homes, captioned “1956 | strikes outlawed.” Composed of selectively excerpted, cropped, and framed photographs, The ARD: Study for a Portrait testifies to the alluring existence and yet inaccessibility of histories unknown.

The ARD: Study for a Portrait series condenses several of Waheed’s abiding artistic interests and approaches. The ARD, or Arabian Research Division, of oil giant Aramco, was established in 1946 as the company’s in-house research team that studied the land and local tribes along the oil-rich northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in order to control allegiances, exploit resources, and solidify national borders. Waheed’s compositions implicate the ARD’s territorial surveys in processes of disposition, while dissent or resistance to the joint Arabian-American enterprise was crushed and suppressed, a history that remains little known or told. In that sense the “portrait” of an organization at the center of the global economy is still a provisional one.

These stories—lost, missing, and vanished—of Saudi Aramco are also interwoven into Waheed’s biography. Born in Calgary in 1980, and now based in Montreal, Waheed spent her childhood and much of her adolescence living in Dhahran, on the gated Saudi Aramco compound where her father worked as a geologist. In a 2017 lecture at Montreal’s Concordia University, she describes the company’s base as one of “the most protected and restricted sites on the planet,” guarded by the CIA and Saudi security services, and with strict prohibitions on the use of photographic and video equipment. These restrictions produced “undercurrents” to the questions she asked as a child, even leading her to record her observations about life at Aramco in what she calls a “cryptic visual language.” Meanwhile the first Gulf War (1990–91) was happening overhead, with Saddam Hussein’s army firing Scud missiles at sites including Saudi Arabia’s air force base in Dhahran.

The aerial perspective is crucial in Waheed’s work. From a young age she was fascinated by tracking aerial vehicles. The silhouettes of aircrafts are evident in several of the series comprising her Drone Studies (2011– ), including Architectural Studies 1–17 (2011), in which she juxtaposes the plans of historical mosques with diagrammatic fragments of wings or fuselages from Cold War-era U-2 spy planes. Produced nearly a decade ago, the Architectural Studies reflect an era when the world was just beginning to learn details about the covert drone programs run by the CIA in the “war on terrorism” that brought terror from the sky to predominantly Muslim regions of the world. This hovering occupation from above embodies the new securitization, mapping, and surveillance, all occurring within the range of a few thousand meters.

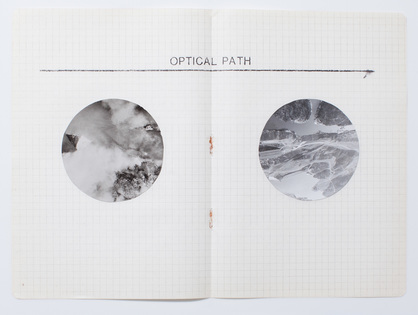

Waheed’s interest in the history of scopic technologies and their origins in the Cold War led her to explore other orbits of the earth’s surveillance. She produced KH-21 (2014), a series of 32 collages made with photographic cut-outs and xylene transfers onto graph notebook pages, by drawing on materials from the 2011 declassification of the United States’s KH-9 Hexagon Reconnaissance Satellite campaign, which monitored the Soviet nuclear missile program with 20 photographic satellites launched between 1971 and 1986. KH-21: Notes 17/32, for instance, mirrors the satellites’ stereographic cameras with two photographs of the earth seen from above cut into circles with a hand-drawn arrow running above them marked “optical path.” The installation of the series also featured a large steel orb that sat in the gallery space like it had fallen from the sky; musician Laurel Sprengelmeyer composed a soundtrack for the object’s imagined journey, played on a mono-pod headphone.

Installation view of The Cyphers 1-18, 2016, found object, cut collage, ink and pencil on paper, dimensions variable, at “The Cyphers,” Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo by Colin Davidson.

In KH-21 and a subsequent project The Cyphers 1–18 (2016), the fragments of images, text, and objects become tantalizing vessels for information. The Cyphers 1–18 is laid out on a plinth like evidence from a crash site, with stray mechanical pieces, as well as scraps of metal and plastic. Around these objects are 18 collages, what Waheed calls “notes,” that viewers can examine in order to piece together “a larger story of secrecy and surveillance.” Written on mechanical drafting paper from the Douglas Aircraft Company—an American aerospace manufacturer that became McDonnell Douglas, one of the US government’s primary sources for military technologies during the Cold War—each note is signed by a mysterious, “para-fictional” persona named “R.E. Moon” and comprises technical drawings of devices, some recognizable, others not, and annotated photographs showing, for example, an aerial view of a city or the base of a mountain. The work plays on our assumptions about the capacities of materials to provide facts, yet the fragments point to the volume of what remains unknowable or secret—like so much of the classified history of our contemporary national-security states.

The importance of the sky in Waheed’s work is matched by the significance of water and land, seen and traversed from a human perspective. A parallel project to her Drone Studies is Sea Change (2011– ), which she describes as a “visual novel about the missing and the missed.” The first of nine chapters, Character 1: In Rough revolves around a geologist in search of quartz. In A Short Film 1–321 (2014), a collage featuring a man standing in a boat, below a sky of water and rocks, is seen through a glass oculus mounted on a pedestal. Running across the walls behind the pedestal were wooden shelves lined with 321 collages—of geological features excerpted from photographs—placed in glass-slide viewers. The journey is the geologist’s but also ours, as we scan the landscapes for information. “Like flotsam and jetsam of a shipwreck, thousands of these fragments, or works, will, over the course of a lifetime, come together to form these visual memoirs,” she explained in her 2017 lecture.

Detailed installation view of A Short Film 1–321, 2014, 321 negative glass slides, cut photographic collages, custom wood shelving, 14 × 17 cm each, at “Viva Arte Viva,” 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo by Francesco Galli.

When Waheed exhibited A Short Film 1–321 at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, Italy, Greece, and the coasts of southern Europe were awash with tragic stories of thousands of refugees losing their lives during their crossings. It was impossible then to look at Waheed’s series of small gouache paintings of blue-green waves, Our Naufrage 1–10 (2014), and see anything but the deathly silence of watery graves. Framed in brass and mounted on poles rising from wooden pedestals in three rows, the ten paintings evoked the small placards on sticks used in Turkey, France, and elsewhere to mark the burials of perished migrants. The work echoes Arundhati Roy’s poignant formulation in her 2004 acceptance speech for the Sydney Peace Prize: “There’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless.’ There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.” The “Naufrage”—meaning “shipwreck”—of the title refers not just to those vessels that sunk in the Mediterranean and Aegean but ours collectively. The figures of the lost are part of a larger history only beginning to be told in Achille Mbembe’s analysis in Necropolitics (2019) of how fledgling Enlightenment-era democratic states exported their intra-community violence to their colonies where it continues to this day in the form of deportations, discriminations, and a willful blindness to “refugees and all the shipwrecked.” Meanwhile, the tides are rising, very literally in Venice, and the many other places in the world threatened by the changes in climate that contribute to the most dangerous mass migrations of our era.

The surfacing of vanished figures recurs throughout Waheed’s works. “We tend to forget our relationship to time. Whether desert, sea, or sky, each vast expanse carries with it the past, the eclipsed, the refused, the silenced, the disappeared,” Waheed says. Accompanying A Short Film 1–321 at the 57th Venice Biennale were 38 small paintings on wooden shelves. Each just 13 by 18 centimeters, the paintings of Avow 1–38 (2017), which she calls “a series of apparitions in the night,” were inspired by ex-voto paintings left in churches. This progression of images includes renderings of smoke plumes, burning oil fields like those in Kuwait and Iraq during the Gulf War, a pair of hands holding red poppies, a fish on a platter, a storm out over the sea, and a meteor burning through the sky. All these images are punctuated by paintings of stars, like a person’s flashes of memories that arrive at night, while they are trekking across the land or drifting across the sea.

Waheed’s exploration of interlaced historical legacies—such as that of Cold War military infrastructure and Obama-era drone programs—is ongoing. She has described the Saudi Aramco compound as a “microcosm of the colonial order” and said it provided her with an “acute understanding of the macro issues we continue to face.” The ties between the displacement of people from their lands by wars over resources with climate change and state-monopoly capitalism brought about by fossil-fuel extraction is visualized in Untitled (MAP) (2016). The 160-centimeter-long drawing on a vellum paper is folded in jagged peaks resembling the reverberations of sonic waves and is exhibited horizontally on a plinth. The image is based on a classified seismic survey of the world’s largest offshore oil reserve near Dhahran. Visually, Untitled (MAP) connects a high-tech form of undersea mapping with the macro-level abstractions integral to the contemporary commodities trade, with prices measured on rising and falling indices, placing raw information at the center of complex systems that explain but also obscure our world.

The progression of Waheed’s political synthesis of the strands of colonialism, fossil-fuel extraction, war, and other crises led to a fully articulated narrative performance-lecture titled Hold Everything Dear at Asia Contemporary Art Week in November 2017 and at Sharjah Art Foundation’s March Meeting in 2018. There Waheed sat in front of an overhead projection of a large black mass of paper that she manipulated over the course of her monologue, which began with a letter from her sister dated November 16, 2015, just a few days after the Paris attacks and subsequent backlash against Muslims in France. “And around and around and around it all goes. An eye for an eye, leaving everyone blind,” begins the grimly prophetic text on generational cycles of violence. The text then traces a narrative of “the other” who colonizes a population, leaving its society wrecked, blames it for the violence and then stigmatizes its culture. At the end of the performance, Waheed unfolded the black paper to cover the screen, with only pinpricks of light shining through, returning to an image of the night sky.

Installation view of (left) A River Runs Beneath, 2019, cyanotype on linen, 147.3 × 155 × 152.4 cm; and (right) How long does it take moonlight to reach us? Just over one second. And sunlight? Eight minutes, 2019, sunned paper, 28 × 35.6 cm and 122 × 132 cm, at “Hold Everything Dear,” The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, 2019–20.

If the performance Hold Everything Dear marked an aporia of despair about the recurring violence stemming from colonization, her 2019 exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto of the same name traced its redemption. “Hold Everything Dear” drew its title, and spirit, from John Berger’s 2007 collection of essays, in which he explores the idea of “‘undefeated despair’ and the possibilities for radical hope.” While Waheed’s earlier concerns about the infrastructure of surveillance were evident at the show, many of her new works “visualize modes of resisting and overcoming tides of violence and despair.” She debuted a series of delicate ceramic works of miniature ladders propped up against walls, evoking border barriers in Palestine, the US, and Europe; a series of etchings, including one of two hands gripping each other by the wrist, in what she calls “the strongest and most enduring human hold-bond, especially in matters/times of survival”; nine individual paintings on tin of a single cloud formation that represent “the defiance of dreaming while in a state of imprisonment”; and a series of illustrated letters from an activist working with labor and peasant groups in Malaysia to recover land expropriated for palm oil plantations. Her cyanotype on a bolt of linen that flows from a fixed point on the wall onto the floor, A River Runs Beneath (2019), and a composition of faded sheets of paper exposed to light for different durations evoke the power of the sun’s energy to provide “a slowly building source of life” in contrast to fossil fuel consumption. Arrayed across four shelves, Studies for a Starry Night 1–94 (2019) are diversely shaped pieces of glazed porcelain and stoneware that represent “one sky broken into different vantage points.” As Waheed describes the exhibition, “The interplay between the individual and collective action is something that is always at play in this body of work.”

The unfolding sentiments of connectivity, community, and the “power and will of individuals and unarmed people” expressed in her video-poem The Spiral fed into her latest work, a sound installation titled Hum (2020). Carrying the dual meaning of “we” in Urdu and originally conceived for the Lahore Biennale 02, Hum was situated in the Diwaan-i-Aam, a colonnade space built by Shah Jahan in 1628 inside the historic Lahore Fort as a place where the public could come to air their grievances. Now, under Pakistan’s heavy militarization, it is an entirely inert, silent space. Within the historical archways, Waheed suspended speakers that play a 16-channel sound work, 36 minutes in length, that combines the hummed melodies from eight songs into a single, wordless chorus. Subsequently reconfigured for Portikus in Frankfurt, Hum features songs that were instrumental in solidarity movements and banned by oppressive regimes over the course of decolonization struggles, ones that continue today. The composition begins and ends with melodic excerpts by Nûdem Durak, a young Kurdish woman from the besieged city of Cizre who was sentenced to prison by the Turkish state for 19 years in 2015 for “promoting Kurdish propaganda” because she was teaching children folk songs in their community’s native language. Stripped of their words, the hummed refrains resonate in the minds of those who know them, becoming an abstracted but still audible means of resistance, and “an utterance we are all capable of making even when our lips have been sealed shut.”

While Waheed was preparing Hum in late 2019, students in Pakistan were engaged in mass protests and were targeted for arrest under vestigial colonial laws, including those banning “sedition.” At the same time, anti-communal activists in India were protesting against a new law offering citizenship to refugees of any religion except to Muslims. Waheed observed that movements on both sides of the 1947 Partition were reciting Urdu poems of resistance by Habib Jalib and Faiz Ahmad Faiz—including the latter’s ghazal “Hum Dekhenge” (“We will witness”), famously sung by Iqbal Bano in a 1985 Lahore concert in defiance of the dictator General Zia ul-Haq’s ban on Faiz’s poetry—and that though they were not actively coordinating with one another, they were “communicating across time and space.”

In Waheed’s works of a decade ago, global mapping and state-sponsored surveillance were the technologies that bridged history and distance; more recently it is human awareness and solidarity. The recurring image in her practice of the night sky embodies these many resonances. In Still Against the Sky 1–3 (2015), three folded pages of carbon transfer paper become maps of the stars that a traveler or migrant might have tucked in their pocket to guide them; it also represents a view back at the unseen satellites orbiting above us. That acknowledgement of a presence above us is a universal one, in defiance of our individual circumstances. As Waheed says, “Everything is connected. If you dig at the desert you might find the sea. Dig at the sky, you might find yourself.”

SUBSCRIBE NOW to receive ArtAsiaPacific’s print editions, including the current issue with this article, for only USD 100 a year or USD 185 for two years.

ORDER the print edition of the September/October 2020 issue, in which this article is printed, for USD 21.